A way to observe in comfort

Look at this! On this page you will find a telescope design seldom seen by the observing public. It is a hybrid telescope that combines the best of both refracting and reflecting telescopes. It's especially good for a comfortable view of the night sky, allowing the observer to remain seated.

And that design feature allows easy access to the telescope's eyepiece for parents with small children and for those confined to wheelchairs. I designed this telescope and had it built. But I wasn't the first to do it.

And that design feature allows easy access to the telescope's eyepiece for parents with small children and for those confined to wheelchairs. I designed this telescope and had it built. But I wasn't the first to do it.

Usually we see many observers interested in either the classic refractor (known formally as a dioptric design) or some variation of the reflector (known formally as a catoptric design). The hybrid design on this page is that of a catadioptric, a blend of the refractor and the reflector!

Scroll down for pictures!

Such hybrid designs have been commercially available for decades, either as a Schmidt-Cassegrain or a Maksutov, and, more recently, a Schmidt-Newtonian. All are good and are quite portable. The names of these catadioptrics derive from those who contributed the design idea.

To my knowledge, few have attempted this design, though the ideas for it have been around for hundreds of years! The name derives from the two historical personages that lend their names to the scope's operation.

The catadioptric pictured here is the Mersenne-Nasmyth, and it is not a household name. It is a telescope that I constructed from available parts and with the help of expert machining. To keep it looking nice over time, I had many of the metal parts either powdercoated or anodized.

The telescope's appearance and operation have won design awards for it.

To my knowledge, few have attempted this design, though the ideas for it have been around for hundreds of years! The name derives from the two historical personages that lend their names to the scope's operation.

The catadioptric pictured here is the Mersenne-Nasmyth, and it is not a household name. It is a telescope that I constructed from available parts and with the help of expert machining. To keep it looking nice over time, I had many of the metal parts either powdercoated or anodized.

The telescope's appearance and operation have won design awards for it.

Here's how it got its name:

Marin Mersenne was a French mathematician of the 17th-century and an ardent champion of Galileo and his discoveries. He was also interested in optics and in improving the kind of refractor that Galileo had used to make those discoveries.

He figured that confocal (or, optically matched) mirrors would obviate the need for lenses in a telescope, and he was right. But his good friend, René Descartes, talked him out of pursuing this telescope design!

Instead, Mersenne is likely better known for experiments in tuning musical instruments and in music theory, and, for his Mersenne primes, a special category of prime number important in solving complex computational problems.

James Nasmyth was a 19th-century Scottish engineer, known for his development of the steam hammer, which quickened the manufacture of metal forgings. He dabbled in astronomy, and especially liked viewing the Moon. He even co-wrote a detailed book about it.

He also developed a type of telescope that afforded him a comfortable view of the night sky while seated next to his instrument. By inserting a flat mirror in the light path of a typical Cassegrainian design, he diverted the light path through the declination (or, altitude) axis of his telescope. This allowed a steady and convenient place for the eye to observe. This innovation, known as the Nasmyth focus, is used currently on large telescopes in large observatories.

Here's how it works:

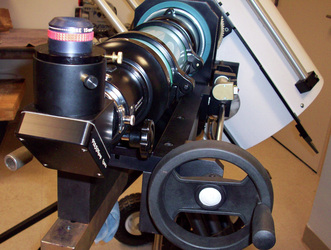

The design I've constructed combines the best aspects of these two gentlemen's designs. With a set of large optics I have crafted, I make use of Mersenne's confocal mirror concept to gather light and bundle it into a tight, magnified beam, and then to feed that bundled beam into a well-made refractor placed solidly at the Nasmyth focus (as shown in photos, below).

The result is no less than a stunning view through a fine refractor that has the large aperture of a fine reflector! Sounds implausible, but it does indeed work. As a side benefit, the telescope affords a comfortable, seated view of the night sky, which makes its unusual optics available to parents with a small child seated on their lap and to persons in wheelchairs, since the eyepiece (above, middle) is placed for relatively easy access.

At present, my telescope is nominally portable when on pneumatic wheels, but does take a little while to set up if it were to visit a star party. Collimation is necessary but not impossible to accomplish, even though this catadioptric system utilizes a total of four internal reflections, which results in a normal (i.e., inverted) telescopic view.

Here's how it started:

For those who must know, the 17.5"-wide main mirror was originally made by Coulter Optical, but had unfortunate polishing flaws prior to its aluminization, which were clearly visible with a Foucault tester. (The figure looked like an old vinyl phonograph record, with hundreds of rings left from incomplete machine polishing!) I had the optical services of Clausing's in Skokie, Illinois, remove the old shiny coating before I set to repolishing the big glass.

With the expert help of Jim Seevers at the former Optical Shop of Adler Planetarium in Chicago, I re-polished and re-figured the big glass to a fine optical surface better than one-tenth wave. The four-inch wide secondary mirror took time to complete, but it's a confocal match to the main mirror, which means its optical figure is an exact complement to the main's figure.

With the expert help of Jim Seevers at the former Optical Shop of Adler Planetarium in Chicago, I re-polished and re-figured the big glass to a fine optical surface better than one-tenth wave. The four-inch wide secondary mirror took time to complete, but it's a confocal match to the main mirror, which means its optical figure is an exact complement to the main's figure.

Here's what happened next:

I arranged the optical components in a typical Dobsonian design, since my first attempt at constructing a Mersenne-Nasmyth scope was an instrument of dual perspective, that is, it was combination of Newtonian and Mersenne-Nasmyth optical designs.

So, this first telescope, a proof-of-concept model, was convertible from one optical configuration to another. Both modes of operation still allowed seated observation.

My proof-of-concept model was first built of plywood twenty years ago and was displayed at various star parties around the Midwest. (See it at right.) That concept model nested nicely to be portable, traveled well enough, and won design awards as well.

So, this first telescope, a proof-of-concept model, was convertible from one optical configuration to another. Both modes of operation still allowed seated observation.

My proof-of-concept model was first built of plywood twenty years ago and was displayed at various star parties around the Midwest. (See it at right.) That concept model nested nicely to be portable, traveled well enough, and won design awards as well.

Here's how it's progressed:

Having learned much about how to utilize the plywood prototype, I sought to improve its overall operation. Eventually, I had the plywood prototype rebuilt and machined in aluminum by Industrial Machining in South Chicago Heights, Illinois. And they built a superb instrument, crafted to high tolerances.

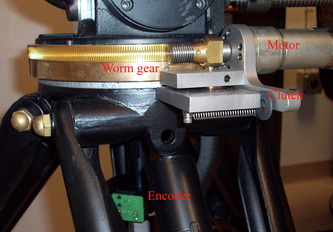

Clausing resurfaced both the primary and secondary mirrors with a bright coating and all of the components were fitted into the upper and lower tube assemblies. A central plate and main axle allow the assembled components to swing in azimuth while steel and bronze gearing raise or lower the tube assemblies in altitude. The sturdy tripod (from Houston Fearless) on which everything sits was once used in a TV studio; years ago I bought it in a camera store in Urbana, Illinois, for just $100.

In the photos (above, and at lower right), that's a sky-blue Brandon refractor shown, one of the first 50 manufactured by Roland Christen. One must have a fine refractor to make this all worthwhile.

Clausing resurfaced both the primary and secondary mirrors with a bright coating and all of the components were fitted into the upper and lower tube assemblies. A central plate and main axle allow the assembled components to swing in azimuth while steel and bronze gearing raise or lower the tube assemblies in altitude. The sturdy tripod (from Houston Fearless) on which everything sits was once used in a TV studio; years ago I bought it in a camera store in Urbana, Illinois, for just $100.

In the photos (above, and at lower right), that's a sky-blue Brandon refractor shown, one of the first 50 manufactured by Roland Christen. One must have a fine refractor to make this all worthwhile.

Here's where it's at today:

The re-built scope is my engineering prototype. (See it at right.) Incoming light is compressed and magnified by the confocal mirrors, and directed to the observer by two flat mirrors, one above the main mirror and a quartz flat inside the refractor. One can remain seated while observing.

I've written articles about this design, which you can find in back issues of Amateur Astronomy Magazine; and, I've presented many talks about its increasing usefulness as a stable platform for astrophotography and for simply viewing in comfort. It's not a dream telescope, but it has much to recommend it.

There's more to tell about this design. I'll be adding to this page as I make improvements. I believe it's likely that certain large Dobsonian-style scopes can be retrofitted with the right components to convert them to this catadioptric design. Also, there is potential for making fine refractors perform even better. Let me know what you think.

I've written articles about this design, which you can find in back issues of Amateur Astronomy Magazine; and, I've presented many talks about its increasing usefulness as a stable platform for astrophotography and for simply viewing in comfort. It's not a dream telescope, but it has much to recommend it.

There's more to tell about this design. I'll be adding to this page as I make improvements. I believe it's likely that certain large Dobsonian-style scopes can be retrofitted with the right components to convert them to this catadioptric design. Also, there is potential for making fine refractors perform even better. Let me know what you think.

So, for additional info:

I wasn't the first to build this kind of scope; I'm the second. But I am the first to make improvements that can make this scope even more useful to both casual stargazer and serious amateur astronomer. More on that later. In the meantime, here are two shots of the scope in action at my prime viewing site, the OAAO.

What's the OAAO? It's the Open-Air Asphalt Observatory, also known as my driveway.

The telescope is fairly portable on its pneumatic wheels. Of course, setting it up at a star party takes time.

The telescope made its most recent appearances at various star parties in the Midwest. And though it does take a little time to set up properly, it's worth it.

The telescope made its most recent appearances at various star parties in the Midwest. And though it does take a little time to set up properly, it's worth it.

Finally, here's what started it all:

The first person (and only other person) who I know to have built this kind of scope is one named Clyde Bone. The late Mr. Bone (he died in 2012) is pictured (at left) at the Stellafane star party in 1994 with his own 20-inch home-built Mersenne-Nasmyth telescope. Neatly constructed, isn't it? Note that he can enjoy the night sky while seated in comfort alongside his instrument.

His story is found in an article published here by TeleVue Optics, Inc., in 2019. Other astronomical periodicals might have back issues of articles like this, but reprints may be pricey. Bookmark this page. Come back soon.

His story is found in an article published here by TeleVue Optics, Inc., in 2019. Other astronomical periodicals might have back issues of articles like this, but reprints may be pricey. Bookmark this page. Come back soon.

Want to know more?

R. A. Kaelin, a native of Illinois, teaches astronomy and other natural sciences, encouraging his students to appreciate the splendors of the night sky from Midwestern locales. He has become an ardent supporter of the catadioptric telescope design, known as the Mersenne-Nasmyth, which can help more observers access and appreciate the night sky. He has gathered together information about this distinctive design in a concise book, All Done With Mirrors, found on his companion website here.